5

minute read

Listen to the True Spies Podcast COINTELPRO Part 1: The Black Panther Plot

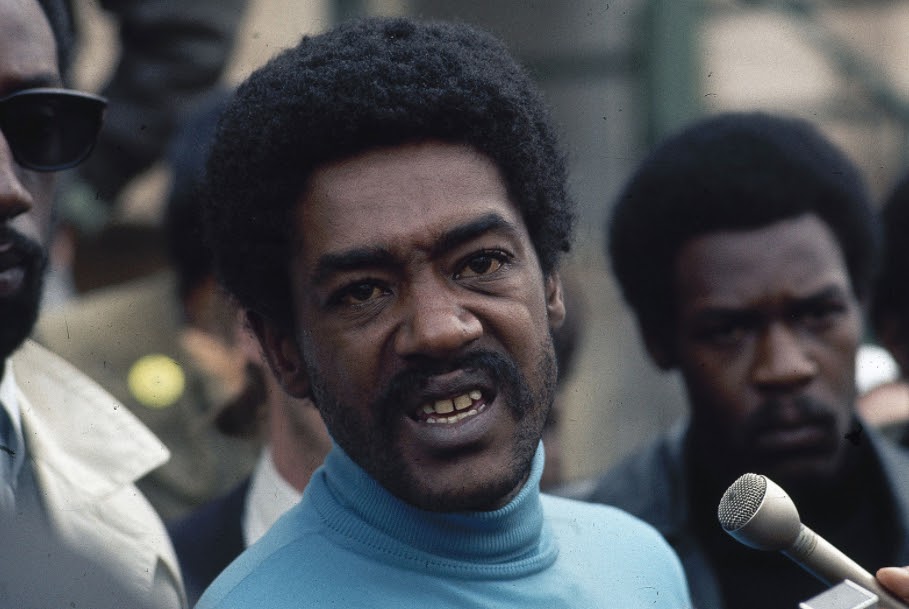

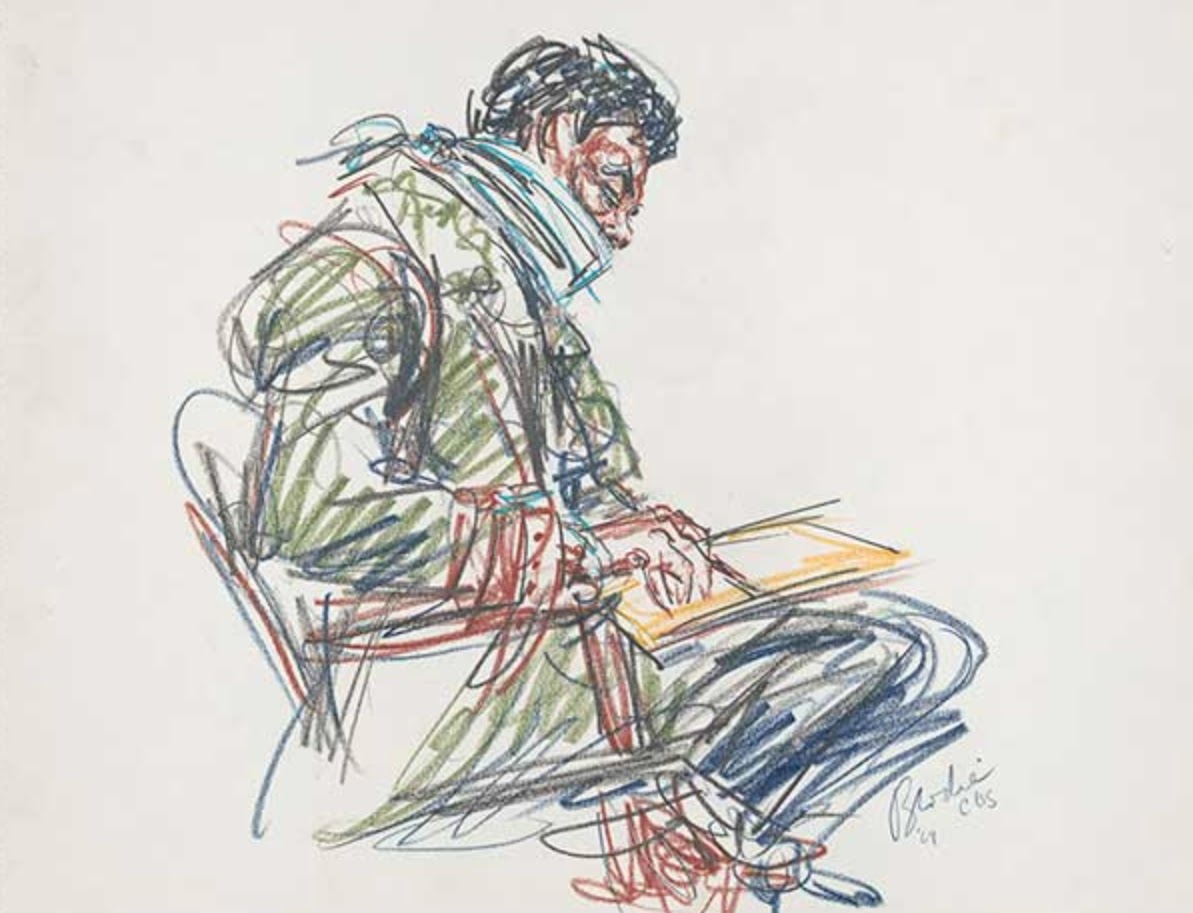

Bobby Seale was 33 when he was gagged, shackled to his chair and wheeled into a Chicago courtroom to face charges linked to a riot during the 1968 Democratic Convention.

More than 50 years later, director Aaron Sorkin captured his struggle in Netflix’s The Trial of the Chicago Seven, but the real-life events that inspired Sorkin’s movie are even more disturbing than the film, raising questions about liberty, justice and the US intelligence community in the 1960s.

Bobby Seale: the Vietnam years

Robert ‘Bobby’ Seale was born in 1936 to a poor family that drifted from Texas to California. He dropped out of high school and joined the US Air Force only to be court martialed and convicted of fighting with a commanding officer at Ellsworth Air Force Base in South Dakota, resulting in a bad conduct discharge. Seale found jobs as a mechanic and even worked on the Gemini missile project in California but nothing stuck.

"I quit that job 15 months later because the [Vietnam] war was going on and I felt I was aiding the government's operations,” Seale said in his autobiography, Seize the Time. 'I wanted to go to Africa by that time. I was out with the government then and I had become very hip.”

It was the early 1960s, a time of Vietnam protests, tension over the Cuban Missile Crisis, and race riots in Alabama and New York. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech in 1963, but King’s peaceful approach was at odds with other community leaders. Malcolm X urged black Americans to gain freedom, equality and justice 'by any means necessary'.

Seale enrolled at Merritt Community College in Oakland, California and joined the Revolutionary Action Movement, a Marxist-Leninist group that believed violence was the way to free black people. By 1962 he’d met Huey Newton at college. They shared the same political ideology and both had spent time in prison (Newton for stabbing a man with a steak knife). They formed the Soul Students Advisory Committee to end the draft of black men to fight in Vietnam.

Armed and dangerous

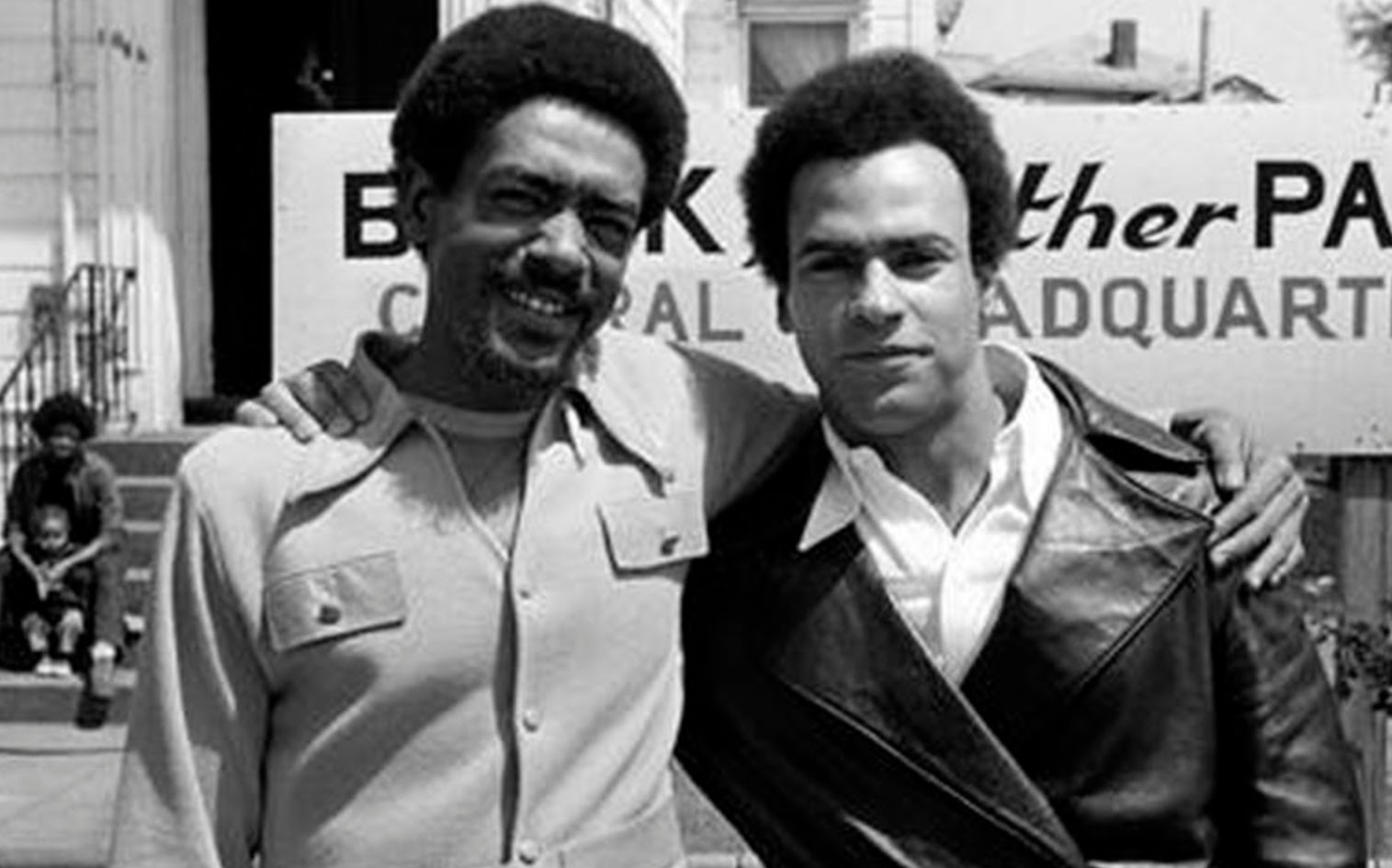

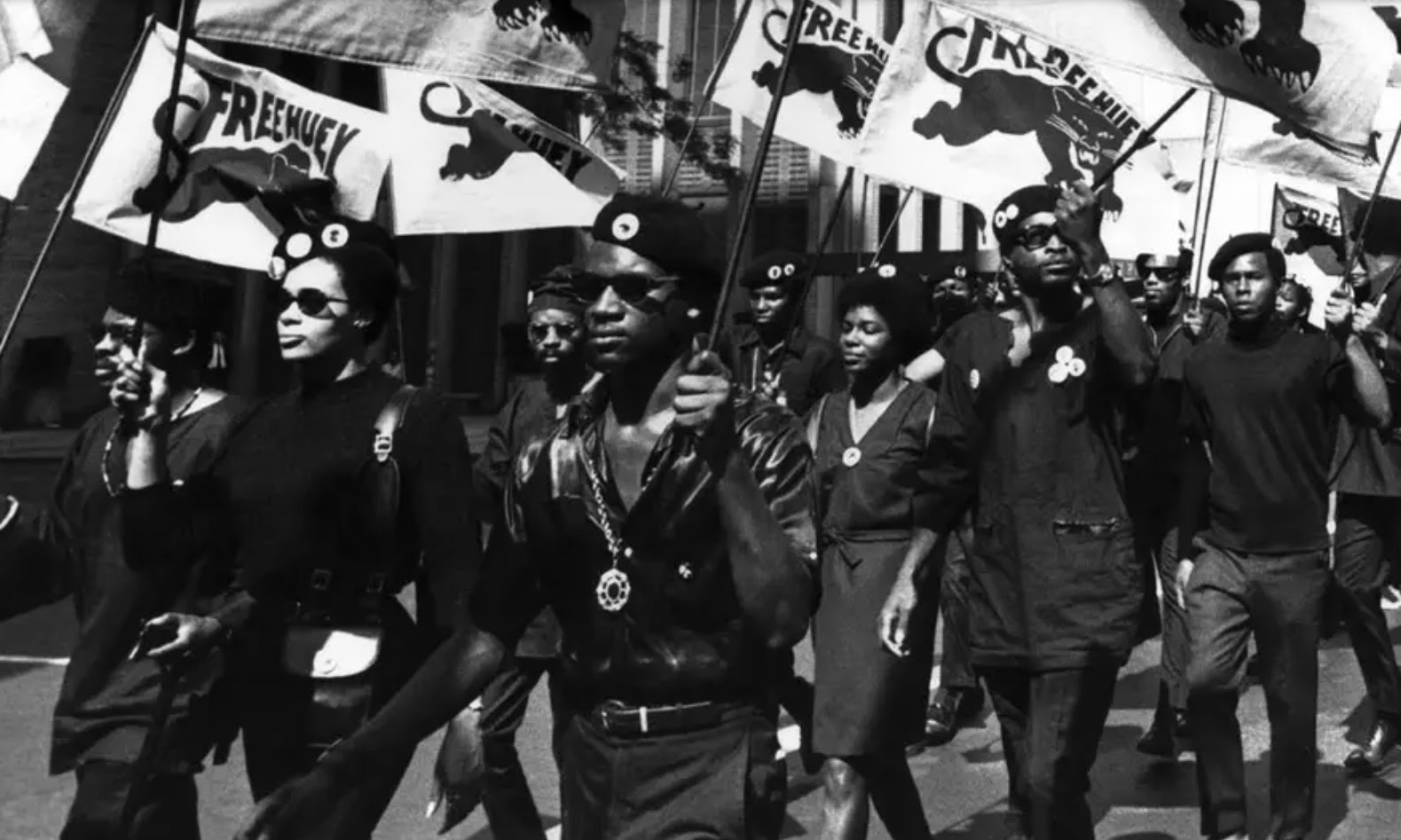

Seale and Newton founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in 1966, a year after Malcolm X’s assassination. Race riots were spreading across the US, eventually making their way west to Los Angeles.

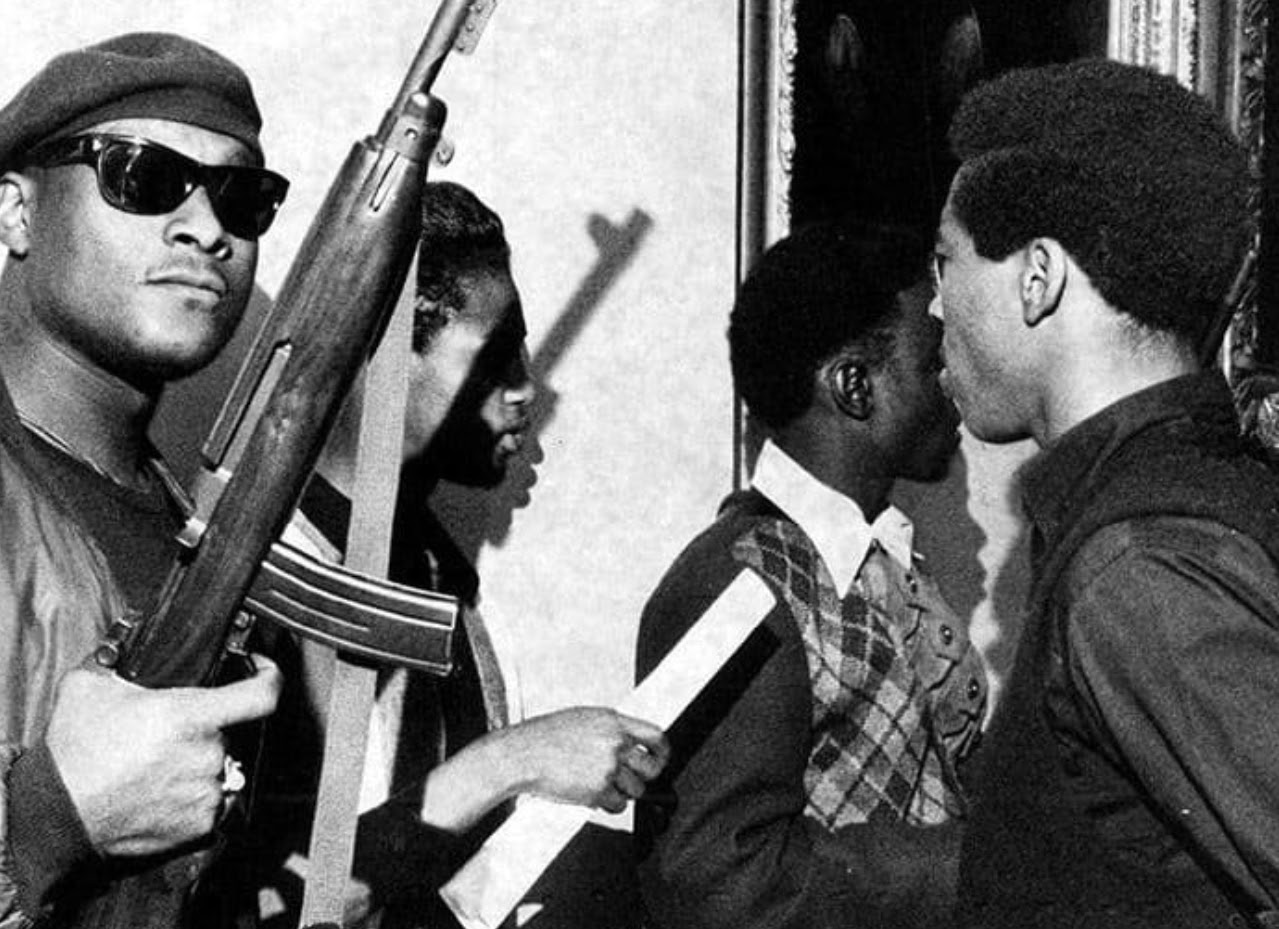

Much of the early US civil rights movement was Southern – church-going men in suits who believed in peaceful resistance – but this new movement was very different. The Panthers were urban, West Coast-savvy and armed. Their uniform consisted of black leather jackets, berets, sunglasses and loaded shotguns. Tom Wolfe described them as ‘radical chic’.

The Panthers would soon become one of the most influential groups to tackle racism and inequality in America’s history.

The Black Panthers investigation

By day, the Panthers ran breakfast clubs for children, opened clinics, and taught black history. By night, they patrolled neighborhoods with weapons looking for police brutality, a routine known as ‘cop watching’. In 1967, the Panthers made national headlines when they entered California’s State Assembly with guns to demand the right to carry loaded weapons in public.

The Panthers grew quickly into a revolutionary group that called for the arming of all black and African Americans. Newton was named Minister of Defense. Seale was Party Chairman. At its height, the Panthers had more than 5,000 members and 60 percent of them were women.

Not surprisingly, the CIA and the FBI were paying close attention. A year before the 1968 Chicago riots that landed Seale bound and gagged in court, the intelligence agencies were already paying informants and bugging the Panthers.

The FBI and CIA spy programs

The FBI’s illegal, covert Counterintelligence Program began spying on suspected Communists in 1956 and expanded to the Black Panthers and beyond. Even Martin Luther King was an FBI target when King was involved in the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott over racial segregation. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover was convinced the Communists had influenced him.

Although Hoover’s goal was to infiltrate and discredit groups he deemed a threat to US security, a US Senate select committee decided the FBI had acted illegally and reprehensibly: “Whatever opinion one holds about the policies of the targeted groups, many of the tactics employed by the FBI were indisputably degrading to a free society,” the senators said in their damning 1976 report.

The FBI tactics included sending anonymous letters designed to either destroy marriages, implicate black members as police informers or trigger tax investigations. In one incident, the bureau sent an anonymous letter to the leader of a violent Chicago street gang saying Black Panthers had "a hit out for you", hoping he’d retaliate.

“After the Black Panther Party (BPP) emerged as a group with national stature, FBI field offices were instructed to develop ‘imaginative’ and hard-hitting counterintelligence measures aimed at crippling the BPP,” the committee found.

Covert action

The FBI eventually admitted to almost 2,300 covert disruptive acts against Americans, which included initiating warrantless break-ins and spreading misinformation. In a few cases, the FBI helped to falsely arrest and imprison activists.

Black Panther leaders Elmer Gerard ‘Geronimo’ Pratt and Dhoruba al-Mujahid bin Wahad spent years behind bars before being exonerated. Pratt, jailed for 25 years for murder, reportedly settled his case against the FBI for $4.5m. Bin Wahad, convicted of wounding two police officers in a gunfight, reportedly settled for about $490,000.

While less is known about the CIA’s methods, the Agency had its own domestic espionage project called Operation CHAOS.

The New York Times, citing unnamed ‘high-level agency officials’, said the CIA recruited black Americans in the 1960s and early 1970s to spy on Black Panther members in the US and Africa. The CIA said its goal was to see if black activists were financed and directed by Communist governments.

In 1969, police shot dead more than two dozen Black Panthers in gunfights. More than 700 were later arrested for a variety of offenses and the political party began to fade away.

The Trial

How accurate is Sorkin’s portrayal of Bobby Seale’s case in The Trial of the Chicago Seven? Sorkin calls it a broad brushstroke ‘painting’ rather than a photograph. (The film’s timeline was changed and the female undercover cop who lured Jerry Rubin was a plot invention).

Seale was bound and gagged in court, however. The evidence against him was slim – Seale hadn’t participated in planning for the Chicago protests and was a last-minute, replacement speaker.

“His whole face was basically covered with a pressure band-aid, but he could still be heard through it trying to talk to the jury,” co-defendant Rennie Davis later recalled.

Bobby Seal and the Chicago Seven

Seale’s case was declared a mistrial but he was sentenced to four years for contempt of court. (He called the judge a 'pig’, among other names.) While Seale was imprisoned, he was accused of ordering the murder of Alex Rackley, a fellow Panther and suspected police informer. The jury couldn’t reach a verdict, however, and Seale walked free in 1972.

Seale’s co-defendants - the 'Chicago Seven’ - were also accused of federal charges involving crossing a state line and conspiring to create a riot during anti-Vietnam War demonstrations outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Five were convicted but the charges were overturned on appeal.

Judge Julius Hoffman also doled out 170 contempt citations with sentences ranging from two-and-a-half months to more than four years for William Kustner, a lawyer who compared the gagging of Seale to events in a medieval torture chamber. The sentences were later overturned.