5

minute read

Spymaster Georg Nicolaus was a German army captain and banker who’d worked in Colombia, South America, the perfect candidate to form a Latin American network to spy on the US in WWII.

Colombia was an important base for the Nazis - a source of platinum for the war industries, strategically located next to the Panama Canal and home to 5,000 Germans. Mexico was also well placed to spy on its northern neighbor. At least 50 Nazi agents were operating on the US-Mexican border in the early 1940s including three espionage rings answering to Berlin, Hamburg, and Cologne.

Nicolaus was sent to Mexico in 1939 to collect intelligence about the US war effort to distribute to agents spread out across South America and Europe. Within a year he would be overseeing the largest of the three spy rings.

Using the code names ‘Max’ and ‘Enrique López’, Nicolaus developed a wide network including Arnold Karl Franz Joachim Ruge, a spy who made microdots, a tiny tool used to transfer vast amounts of intelligence.

Microdot Number 357, for example, informed the Nazis that the US had intelligence about German jets. Following Pearl Harbor, ‘Max’ sent two other letters carrying microdots to Berlin reporting the shape of the upcoming US Navy offensive in the South Pacific and northern Japan, along with the names of battleships transiting the Panama Canal and heading to the Pacific.

The microdot doll

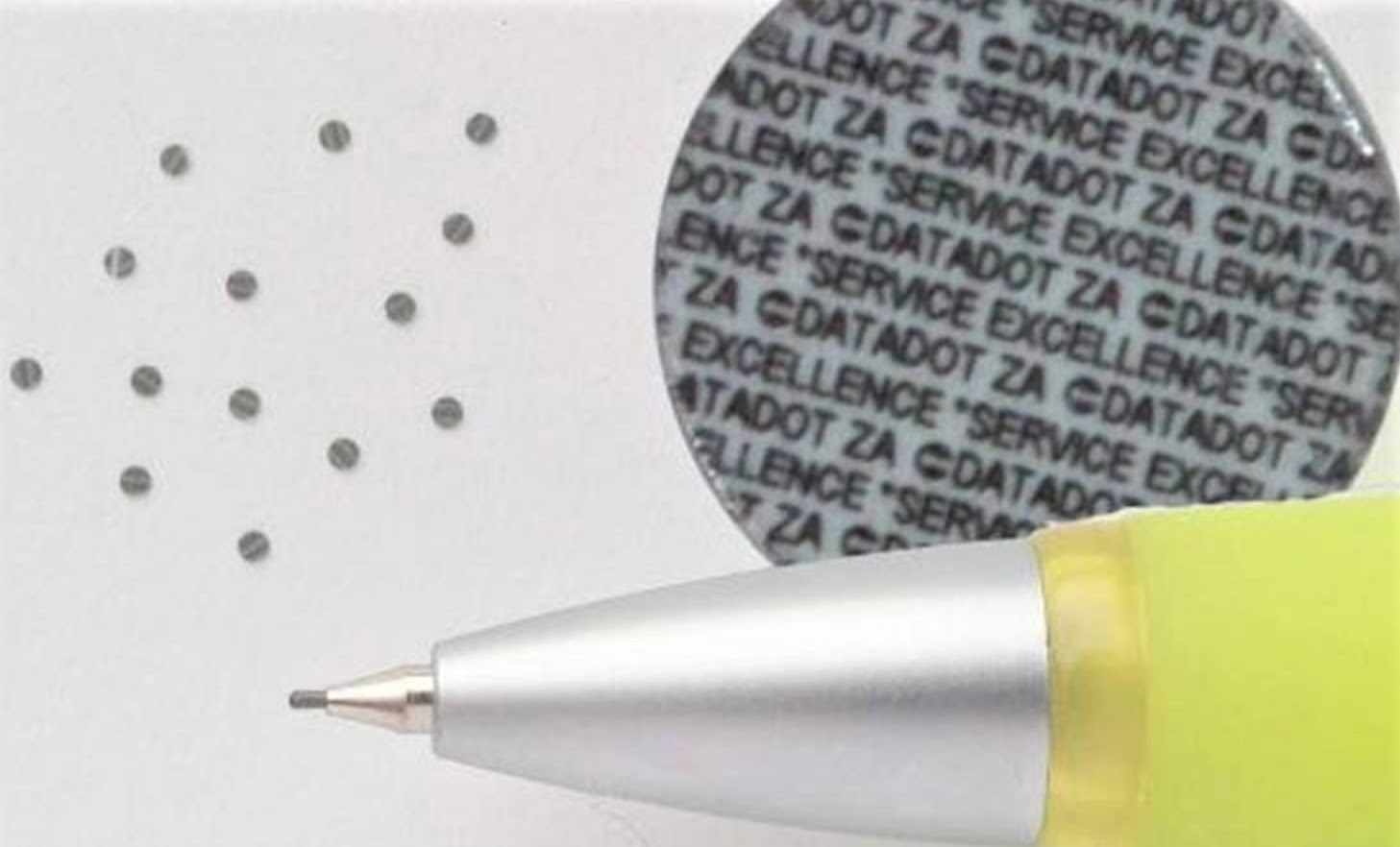

The process of using microdots was highly technical. Spies photographed intelligence and, using special lenses, copied the image, reduced the size and imprinted the information on the sensitized film. Photos could then be reduced to the size of a period at the end of a sentence.

Some microdots were hidden in plain sight, added to correspondence mailed to dead letter boxes - an address that acted as a buffer between the spies and German intelligence headquarters.

Spies also carried microdots into Europe on their clothes or hid them on dolls that appeared to be children’s presents. (Modern spies have taken the microdot a step further and developed a DNA-based technique for sending coded messages.)

By the early 1940s, Nicolaus had recruited a German friend, Max Vogel, to act as a mail intermediary in Colombia.

Nicolaus posted letters containing microdots to Colombia, then Vogel forwarded them to drop boxes in Peru, Chile, Argentina or Brazil, which were then sent either directly to Germany or via Spain and Portugal. Vogel also gathered information on Venezuela’s oil sector for the Nazis, and he sent Nicolaus details about the best way to transfer money to Colombia. The spy ring needed cash.

Although the Germans initially sent Nicolaus to gather economic espionage, the banker concentrated more on naval and maritime intelligence as the war progressed. He had access to a clandestine radio in Mexico City, and he’d been trained to use the latest telegraphic signals and chemical formulas to make explosives.

Nicolaus controlled two agents in the US and had other contacts providing classified information on US bombers and fighter planes, and on the production levels of US oil, aluminum and steel, according to the WWII book Tango Wars.

Nicolaus’ arrest

Josephus Daniels, the US ambassador to Mexico, had given Mexico evidence of spying activities by Abwehr agents - including the tall, blonde spymaster Georg Nicolaus - but President Avila Camacho needed to balance the country’s economic ally, Germany, against its geographic ally, the US. No action was taken until early 1942 following Pearl Harbor.

The spymaster was arrested and sent north where the American were in no hurry to return him to Berlin. Nicolaus had arrived with incriminating items, including concealed microdots.

While the US pressed Nicolaus for information, his colleague Ruge was sent to a Mexican concentration camp. The microdot master managed to bribe his way out, however, and took over as head of the espionage ring reporting to Berlin. The flow of microdot letters and dolls carried on throughout the war. Ruge died in Mexico in 1946 - reportedly by suicide - the day after Ruse threatened to kill any police officer who tried to arrest him.

The spy ring was still in place, however. Acting on FBI information, Mexico told the US ambassador that it had rounded up 21 suspects to be ‘repatriated’ to Germany - kicked out, in other words. As it transpired, only 13 left. The remainder fled or bribed their way out of custody.

As for Nicolaus, the military intelligence officer who’d been awarded the Iron Cross, First Class for his services to Germany in WWI, he remained in the US for at least four years after his 1942 arrest. According to Alicia Gojman, a Mexican historian, Nicolaus was interned in Fort Lincoln, a concentration camp in Bismarck, North Dakota, along with thousands of other German and Japanese prisoners of war.

The Gestapo officer refused to divulge information while the war was ongoing, but the FBI said Nicolaus provided details about Germany’s espionage activities after WWII ended. Little is known about what became of Nicolaus, who was 50 years old in 1945, and the FBI and BND, the German intelligence agency, aren’t saying.

Many of Nicolaus’ Nazi colleagues fled to South America, using the so-called ‘rat lines’ to escape from Germany to Colombia, Brazil and Argentina. The CIA even investigated whether Hitler might still be alive and had used Colombia as his base for several months in 1954 before moving on to Argentina. The theory has been rejected by historians, however, and the declassified CIA memo has been removed from the agency’s website.