5

minute read

The CIA demanded MI6 ‘clean house’ after three senior British spies defected to Moscow.

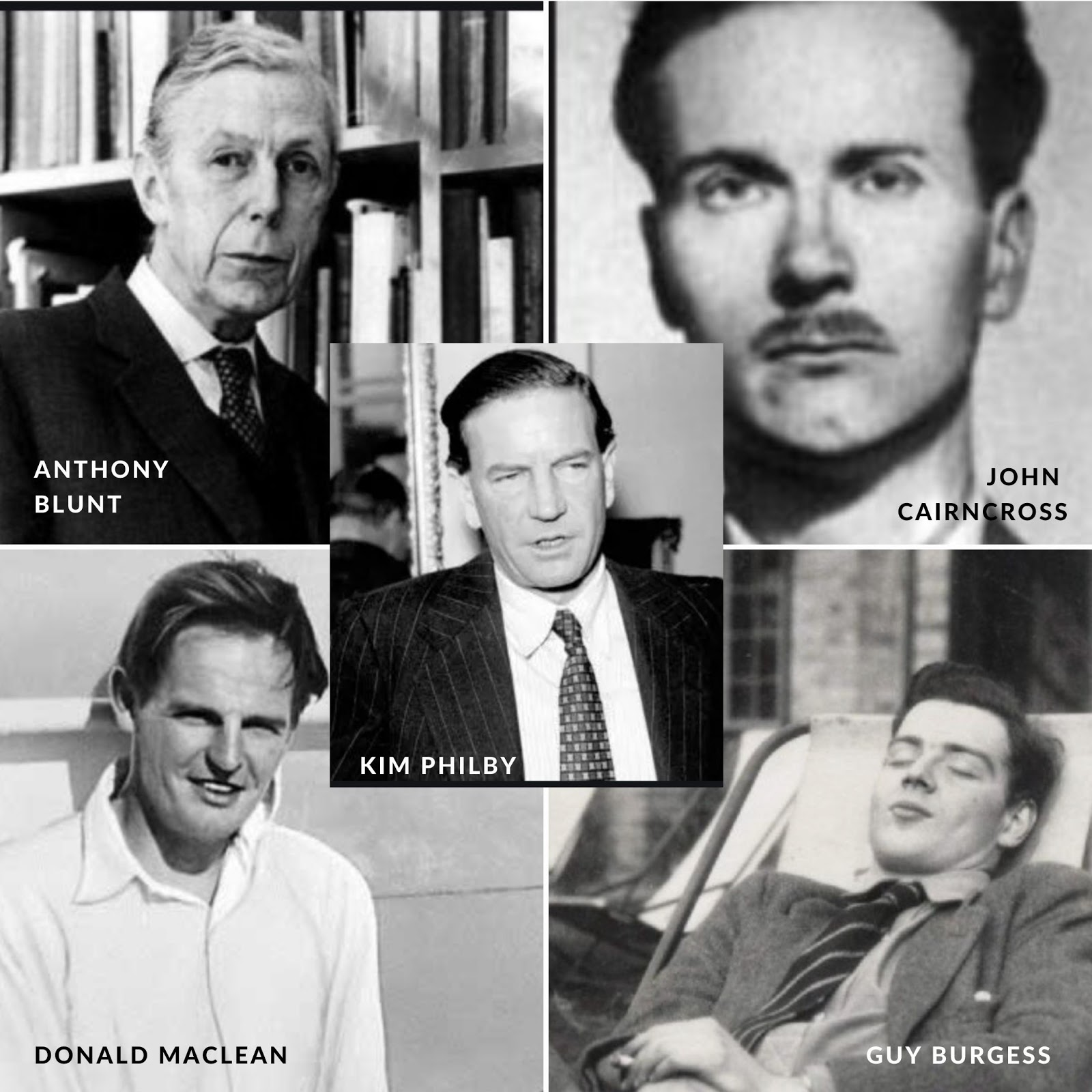

The Cambridge Five: Tension rises between US & British

US confidence in British intelligence nosedived during the Cold War after a ring of Cambridge University-educated spies working for the British government smuggled intelligence to the KGB.

The furor erupted when Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean - two of the so-called ‘Cambridge Five’ - disappeared in 1951. They had defected and later resurfaced in Moscow. Both were hopeless drunks, unstable and promiscuous characters who’d been appointed to top jobs in London and at the British Embassy in Washington, D.C.

The British Embassy reported back that the international incident had “severely shaken the State Department's confidence in the integrity of officials of the Foreign Office".

The Americans pointed out that drunkenness, recurrent nervous breakdowns, sexual ‘deviations’ and other human frailties were considered security hazards and dismissible offenses. Furthermore, the US advised Britain to “clean house regardless of whom may be hurt”, according to declassified papers released by Britain’s National Archives.

.webp)

Kim Philby: The next blow

The unmasking of the first two of the Cambridge Five came a little more than a year after the 1949 arrest of nuclear spy Klaus Fuchs, so the relationship between British and US intelligence was further compromised when Britain was dealt a third blow: Kim Philby, Britain's chief liaison with the American intelligence agencies in the US capital, was a member of the spy ring.

Philby’s betrayal was not just an embarrassment for Britain, it was a threat to US national security.

Philby had worked closely with James Jesus Angleton, CIA chief of counterintelligence, and the Brit liaised with the FBI at a time when director J. Edgar Hoover was convinced Soviet spies were everywhere. Philby had also been briefed on Washington’s Venona project, a program to decrypt top-secret messages transmitted by Soviet Union intelligence agencies including the KGB.

Philby is suspected of tipping off Maclean and Burgess, telling them their covers were blown, but remarkably Philby continued to operate for more than a decade before Philby too defected to Moscow in 1963.

Philby's Memoirs: Panic stations

It is not altogether surprising then that panic set in as Downing Street learned about the next problem in 1968: Philby was shopping his memoirs around through Knowlton, an American literary agent, and it seemed likely his book - My Silent War - would be published or serialized in the US, UK, and France. Philby's friend, MI6 officer and author Graham Greene, would write the introduction.

Among the many secrets revealed, Philby’s manuscript said MI5 bugged the British Communist Party offices in London, according to government papers filed in the National Archives in 2020.

Britain’s secret state swung into action. The UK government conjured up a non-existent French double agent as a red herring to dissuade journalists from looking too closely into Philby’s manuscript. According to the National Archives:

- in 1968 the British government urged the Sunday Times to write about a Soviet agent in France, which the journalists did, suggesting the spy was one of President Charles de Gaulle's staff;

- the Foreign Office’s Sir Denis Greenhill suggested reporters look into Leon Uris’ novel Topaz, which he claimed was based on real Soviet networks operating in France; and

- Roy Jenkins, then home secretary, warned the PM that Philby’s manuscript might expose another mole, Sir Anthony Blunt, the Queen’s art advisor.

.jpg)